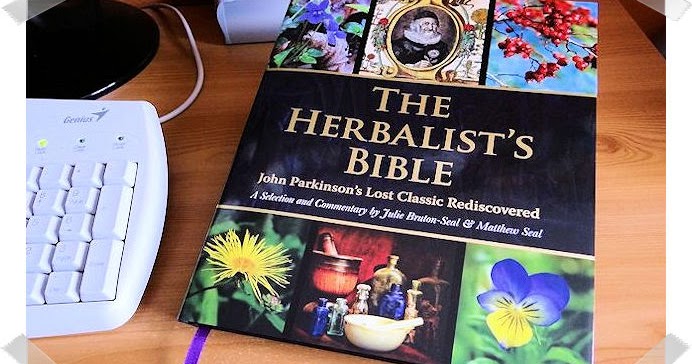

The Herbalist’s Bible Photo © Debs CookThe latest book by Julie Bruton-Seal and Matthew Seal entitled The Herbalist’s Bible: John Parkinson’s Lost Classic Rediscovered falls into the last category and will be read, used and treasured constantly from this day forward. I think it’s also becoming obvious that I’m very interested in herbal history and heritage,and these days most of the articles I write have historical inclusions; be that in the form of facts, quotes, old recipes or references to herbal practices that took place in the past.

I’m rather interested in the way herbal medicine developed and how it was used and viewed during the 16th – 20th centuries but I confess to having a rather soft spot for the 17th century, so much so I can happily pick up a book or transcript written in 17th century English and understand the F for S and other idiosyncrasies of the language of the time and read it with ease. Of the 17th century herbalists the ones most often quoted are Nicholas Culpeper and John Gerard, in part I think, due to the fact that their herbals were easily accessible to the public and are still published in one form or another today.

John Parkinson (1567 – 1650) however is seldom quoted or mentioned these days, which is rather sad, considering that of the three writers of herbals of the 17th century, Parkinson is the one that should stand out. His knowledge and understanding of herbs and their uses far surpassed his contemporaries, and unlike Culpeper and Gerard, Parkinson was an original thinker who ventured forth his own ideas as well as quoting those that came before him.

Given what I’ve just said above, you can imagine how much I squealed with joy when I first learnt that this book on Parkinson was being written, and how thrilled I was when Julie and Matthew asked me to proof read some of the chapters earlier in the year, from the proof-reading I already knew I was going to love the book even before I saw it in its entirety, then my review copy arrived…

Parkinson is known for 2 books the ‘Paradisi in Sole’ and the ‘Theatrum Botanicum’, the Paradisi has been reprinted in the past but the Theatrum has never before been reprinted since it was first published in 1640, not even in a condensed form and condensed this version is. Don’t buy this book expecting to see all of the 1,788 pages of the Theatrum – the biggest herbal ever to be published in English- which looked at over 3,800 plants. Any book that sets out to decrypt and comment on the entirety of the Theatrum, offering modern uses for the herbs Parkinson wrote about and compare how he used the herb with the way we use it today would be double if not triple the size and therefore costly.

What Julie and Matthew decided to do was select 75 chapters from the original book and look at almost 100 plant entries of Parkinson’s. Their choices and outline for the book are explained in the note to the reader on page 22, which outlines what they chose to put in the book and how they decided which herbs to include, using the following criteria:-

1) Herbs that were well known to Parkinson that we still use today like Hawthorn and Saint John’s Wort, although as the authors explain not all the herbs used in Parkinson’s day were used the same way we use them today.

2) Herbs used in the 17th century that would have been very familiar to Parkinson, but are no longer used today, these they dub the ‘lost herbs’ and include Figwort and Sanicle.

3) Herbs selected that were new to Parkinson like Cocoa, Sassafras and Tobacco, herbs he was enthusiastic about getting to know, adding ‘unordered tribe’ and ‘exotic’ chapters to his book to include the herbs from the new world and share his discoveries of those new herbs.

The book begins with a lot of well researched information on the life of John Parkinson, his work as an apothecary, gardener, botanist and author, and paints a pretty clear picture of a well-respected man, dedicated to his craft who was so respected by the higher echelons that he was appointed as “King’s Herbalist” to Charles’s I, unlike Gerard and L’Obel who laid claim to the title but were never officially recognised by the royal court. What we have in The Herbalist’s Bible is an informed and inspired selection of herbs from Parkinson’s Theatrum.

Laid out in a ‘past/future’ kind of way, one side of the book shows Parkinson’s original entry which includes all the ‘Olde English’ spellings, Latin names that Parkinson knew the herbs by, their virtues, uses and the woodcuts used originally by Parkinson. With the addition that under each woodcut there are explanations of terms used by Parkinson and his contemporaries to help you understand your agues from your vulneraries.

On the facing page each herb is named in both English and Latin as it’s known today and its uses in the modern world are described and compared, the way Parkinson used some herbs differs to the way we use those herbs today, for me it was interesting to discover that 17th century herbalists like Parkinson used St John’s Wort as a wound herb and wasn’t familiar with its anti-depressant uses, today we are more familiar with using St John’s Wort for depression than as a styptic. Likewise, today herbalists often prescribed hawthorn as a tonic for the heart, but Parkinson was more familiar with its uses for easing kidney stones and dropsy.

As someone who advocates using those herbs available locally and those that were once used but are now long forgotten, I’m pleased to see that herbs such as the Archangels and members of the Deadnettle family are included, despite the fact that they no longer pay an important part in herbal medicine, they are still used by herbalists for treating many of the same ailments as did Parkinson. Scarlet Pimpernel was once used to treat plague and fevers, but today is viewed as simply a wildflower, Pellitory of the Wall an old remedy for gravel in the kidneys and urinary problems that was still being used in the early 20th century by the likes of Mary Thorne-Quelch who described it as “one of the old remedies which have not been surpassed” and which W.T. Fernie described as “a favourite Herbal Simple in many rural districts” exploring its use for treating dropsy, stubborn coughs and even for bringing relief from toothache. Weld is another herb no longer used medicinal today consigned only to the dyer’s herb garden, yet Parkinson was familiar with its use for bruising, breaking phlegm and as a remedy for the plague, old uses now long forgotten, so it’s wonderful to see them reclaimed for these herbs.

What this book isn’t is a recipe book, if you’re expecting it to be like Hedgerow Medicine with lots of remedies to make at home you’ll be disappointed. That doesn’t mean there are no recipes, within the book you’ll find Parkinson’s take on Aqua-Vitae, the water of life with a modern day version from Matthew and Julie. There’s recipes for Sloe Syrup, Chilli Bread and Jasmine Leaf Oil – which Parkinson recommends for warming the body and for easing pains and cramps, and which Julie uses to make an ointment which she says helps to lighten freckles and liver spots. I’ve made the ointment myself and I’m seeing a definite fading of the liver spots on my hands.Jasmine Leaf OintmentPhoto © Debs Cook

Parkinson was fond of using distilled waters of herbs and many of these like Comfrey, Honeysuckle and Ladies Mantle and their uses and virtues are included, there may not be many actual recipes, but there are lots of ideas for making infused oils, wines and ointments alongside insights for the reader to explore, and herbs to rediscover that will aid them to create remedies à la Parkinson for their own use and get a better understanding of how 17th century herb users used those herbs and remedies.

The appendix of the book for me is a minefield of useful information from and historical point of view, from the explanation of how Parkinson put together his plant ‘Tribes’, to the amounts that he would have paid for his herbs circa 1640. During the late 19th to the early 20th centuries there was a Parkinson revival and in 1884 a Parkinson Society emerged and this is discussed in the appendix, sadly by 1890 it had been absorbed into the Selborne Society an organisation set up in 1885 to commemorate the 18th century naturalist Gilbert White, although the Parkinson information absorbed seems to have been long forgotten. The appendix also gives a timeline for Parkinson from 1564, just before his birth in 1567 to his death in 1650 which highlights of events that happened throughout Parkinson’s life.

There is also a list of what Julie and Matthew refer to as Parkinson’s ‘Firsts’ which is a list of herbs first described by Parkinson in any British Flora, the appendix concludes with brief biographies of the botanists and herbalists that would have been familiar references to 16th and 17th century readers of herbals, listing their roles in herbal medicine, books and discoveries.

For me this book is a beautiful insight in to a man that I’ve respected from afar for a number of years, what Julie and Matthew have done is bring John Parkinson back to life, his book was and is a classic and deserves to be rediscovered be it in part of entirety. The book is visually stunning, highly informative and useful to people like myself who like to learn from our herbal ancestors. I raise my glass of tonic wine to the authors and hope that in the not too distant future they will bring us more of Parkinson’s tribes and thank them for making this great herbal accessible to all once again.

If you can’t wait to get your hands on a copy then the book is available from Amazon (UK) or direct from Julie and Matthew.